I recently returned from a whirlwind of professional travel that wound up providing a particularly apt occasion for writing some commentary on the Regime’s violation of federal court orders and the role of the collateral bar doctrine in the criminal contempt proceedings that may soon get underway.

My travel brought me through seven cities across the country in seven days, not a schedule I recommend. Most of that itinerary involved standard academic professional fare — a scholarly presentation of a work in progress, participation in a discussion panel addressing some of the Regime’s depredations, meetings with former students about career matters — but the last several days were a more meaningful occasion. From Thursday to Sunday I journeyed to Montgomery, Alabama by way of Birmingham to participate in a convening at the Montgomery Legacy Sites which memorialize our shared history of enslavement, lynching, race-based domestic terrorism and government-mandated racial apartheid. The convening was organized by community leaders from Wilmington, North Carolina seeking to advance truth and reconciliation around the 1898 White supremacist coup that massacred scores of Black elected officials and residents of Wilmington, violently overthrew a democratically elected multiracial fusion government, and installed an all-White junta that set a distorted course for North Carolina’s port city for generations to come. Direct descendants of both victims and perpetrators of the coup are a part of this ongoing education and accountability effort and I was honored to be invited to participate in this pilgrimage to Montgomery. The Legacy Sites include three installations: the Legacy Museum, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. All three are remarkable but the peace and justice memorial bearing witness to the atrocity of lynching in the United States is singular, the most brilliantly executed installation I have ever encountered and a devastating, necessary act of durable public witnessing.

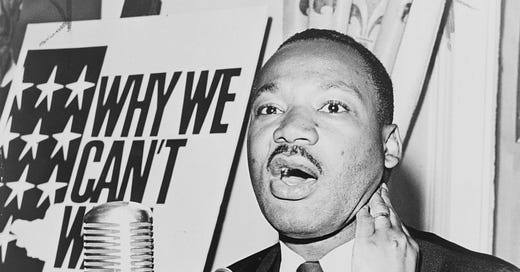

My stay in Birmingham was brief on this trip, just one night in a hotel when I flew into the Birmingham airport before driving to Montgomery and then back through Birmingham on the way home, and my stop-offs there happened to include Good Friday and Easter, a particularly consequential time to be in Birmingham on a civil rights pilgrimage. In early April 1963, advocates from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference including Dr. Martin Luther King, Fred Shuttlesworth and Ralph Abernathy assembled in Birmingham to demonstrate and protest. This Birmingham Campaign aimed to dislodge apartheid in one of the most intractably segregated cities in the country. City officials, most notably Commissioner for Public Safety Bull Connor, reacted with aggression. They arrested Dr. King and others on Good Friday, prompting King to write his Letter from a Birmingham Jail which galvanized support for civil rights, and when advocates organized more protests in response Connor turned high-pressure fire hoses on children and teenagers engaged in lawful assembly, creating some of the most shocking photographs of the movement.

The device Bull Connor used to arrest Dr. King and others was an injunction he obtained from a state court that prohibited protestors from marching. The injunction preemptively carried into effect a Birmingham ordinance that forbade people from marching or demonstrating without first obtaining a permit where issuance of the permit was subject to the arbitrary discretion of city officials. The ordinance was clearly unconstitutional under well established First Amendment precedent. Connor knew, however, that obtaining an injunction might let him circumvent those protections because of the collateral bar rule.

The collateral bar rule holds that a person who is subject to an injunction may not violate the injunction and then defend against criminal contempt charges by arguing that the injunction was illegal or unconstitutional. Rather, the remedy for an unlawful injunction is to raise your objections to the court that issued the order and seek appellate review if that court rejects your arguments. This long-established rule aims to protect public respect for the authority of courts. Because courts have neither armies nor lawmaking authority, public respect for their authority and faith in the deliberative process they use in exercising that authority are indispensable resources. The collateral bar rule prevents people from publicly flouting the authority of courts and instead requires them to subject themselves to that authority even when arguing that their authority has been improperly exercised.

Dr. King and other senior figures in the SCLC had long treated respect for federal court orders as a high obligation. The federal courts had been among the most important government actors in enforcing the protections of the Constitution for Black Americans in the 1950s and 60s. State courts were a different story, particularly in segregationist states. Enmeshed in the legal and social cultures of apartheid and often subject to popular election, state judges sometimes became active participants in subverting the rights of Black people. If there had been no injunction in place, SCLC protestors could have marched and if they were arrested for failing to secure a permit they could have raised the First Amendment as a defense to prosecution under the Birmingham ordinance. Even if state courts failed to enforce their rights they had good reason to hope the Supreme Court would not allow any resulting convictions to stand. There is nothing acceptable about being forced to risk prosecution as the price of marching but the ability to assert those First Amendment defenses provided meaningful protection.

Once Connor obtained his temporary restraining order from the state court, however, the protestors’ speech was legally frozen. If they protested despite the injunction then the collateral bar rule would prohibit them from asserting the First Amendment as a defense to criminal contempt charges. If instead they challenged the injunction in state court they could conceivably prevail but it was all too likely the Alabama courts would view their claims with hostility. Either way, challenging the injunction would take a lot of time and Connor would achieve his goal of preventing the protestors from marching in the moment when marching really mattered.

Dr. King and his colleagues decided to violate the state court injunction, invite prosecution, and use the case as a test of the collateral bar rule, arguing that flagrantly unconstitutional injunctions that would deprive people of well-established time-sensitive rights were not entitled to the same kind of respect. The protestors marched in violation of the restraining order, Dr. King, Ralph Abernathy and several others were arrested by Bull Connor’s men and charged with criminal contempt of court, and the SCLC’s attempt to place some limits on the collateral bar rule eventually became the Supreme Court decision of Walker v. City of Birmingham.

Dr. King and his colleagues lost that fight. By a 5 to 4 vote the Supreme Court upheld the Alabama convictions for contempt and found that even where a state law raised “substantial constitutional issues” as the Birmingham ordinance did, a person bound by an injunction was required to bring their objections to the issuing judge rather than decide for themself the injunction was unlawful and willfully violate it. The Court answered the objections of the dissenting Justices that Alabama officials and judges were flagrantly violating the rights of Black Americans with an emphasis on the vital rule of law principles they believed were at stake:

“The rule of law that Alabama followed in this case reflects a belief that, in the fair administration of justice, no man can be judge in his own case, however exalted his station, however righteous his motives, and irrespective of his race, color, politics, or religion. This Court cannot hold that the petitioners were constitutionally free to ignore all the procedures of the law and carry their battle to the streets. One may sympathize with the petitioners' impatient commitment to their cause. But respect for judicial process is a small price to pay for the civilizing hand of law, which alone can give abiding meaning to constitutional freedom.”

There is ample reason to question the Court’s account of the rule of law here. With Alabama officials and some judges acting in bad faith to shut down civil rights demonstrators, the Court’s reassurance that “delay or frustration of their constitutional claims” by the Alabama courts might create an exception to the collateral bar rule was cold comfort. If the systematic obstruction of officials and courts in segregationist states did not already qualify as delay or frustration then it was hard to imagine what would. For example, the Court pointed to the ruling of one Alabama intermediate appellate court enforcing the First Amendment rights of a different SCLC protestor to justify their assertion that “It cannot be presumed that the Alabama courts would have ignored the petitioners' constitutional claims.” That favorable First Amendment ruling was subsequently reversed by the Alabama Supreme Court in an opinion that ultimately had to be rejected on the merits by the Supreme Court of the United States.

Walker v. City of Birmingham stands to this day as the strongest affirmation of the collateral bar rule. When a court issues an injunction, it exercises a profound species of authority that the Supreme Court has proclaimed to be a cornerstone of the rule of law. Persons bound by an injunction must obey its commands, raise any objections in front of the issuing court, and seek appellate review if they are dissatisfied with the ourcome even if they believe the injunction is unlawful and invalid. Federal and state courts have mechanisms for expedited appellate review of injunctions for exactly this reason.

The current occupant of the presidency, the people in his Regime and their many enablers have loudly expressed outrage at the many injunctions federal courts have issued to stop the Regime’s unlawful conduct, from its extraordinary rendition of immigrants with no due process and punitive attacks on law firms to its cancellation of funds appropriated by Congress and wholesale gutting of authorized federal agencies. Often they object that the injunctions are incorrect, contrary to law, or violate core constitutional principles and seek to justify their apparent violation of those orders by claiming they will ultimately prevail on the merits. Chief Judge Boasberg of the U.S. District Court for Washington DC has issued a finding of probable cause that members of the Regime are guilty of criminal contempt and Judge Xinis of the U.S. District Court for Maryland has repeatedly admonished the Regime for willful violations of her orders. Criminal contempt prosecutions in one or both of cases seem likely.

When those prosecutions do happen, we can comfortably predict the Regime will argue that they cannot be held in contempt because the district court’s injunctions were wrong on the law and hence were invalid. Whether or not they are correct about those arguments on the merits — and it seems clear they are not — Walker v. City of Birmingham stands as a firm rebuke to any suggestion that being right on the law can justify a violation of the rule of law. The collateral bar rule applied to Black leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference advocating for justice in the face of concerted, bad-faith persecution by Birmingham officials and some Alabama state judges. It applies with equal force to the brutal actions of the current Regime.

The searing Montgomery sites are indelible. Kudos to Bryan Stevenson for conceiving them and compelling their construction.

Fascinating, and very clearly stated for lay readers such as myself. Many thanks.